Finding the Balance: Benchmarking Solar, Wind and Energy Storage Community Benefits Agreements

This blog post by the Clean Coalition details community benefits agreements for clean energy projects

Finding the Balance: Benchmarking Solar, Wind and Energy Storage Community Benefits Agreements

By Erik Hagstrom, Haley Weinstein, and Dr. Jon Guice

Summary

This article explores the increasing use of Community Benefits Agreements (CBAs) to address community opposition to renewable energy projects. Over the past decade, renewable energy deployment has surged, driven by policy goals and economic competitiveness. However, community opposition has led to significant project delays and cancellations. To mitigate such opposition, developers have started using CBAs.These agreements, typically involving local governments or community-based organizations (CBOs), specify the benefits a developer will provide in exchange for community support. Benchmarking the funding for these agreements against project capacity helps align community benefits with project economics, although variations in definitions and enforcement create some confusion. By analyzing the lifetime value of clean energy CBAs, academics, local planners, and community based organizations can utilize a benchmark for expected CBA value based on project economics.

While data is still insufficient for definitive conclusions, certain trends suggest effective ways to structure CBAs. Ultimately, CBAs seem to have the potential to create a positive feedback loop by channeling financial gains from renewable energy projects into community benefits, which in turn fosters goodwill and public support for further clean energy deployment. This increased public support can lead to changes in local zoning and ordinances, facilitating more clean energy development creating a self-reinforcing cycle of growth and community engagement in the renewable energy sector. This dynamic underscores the importance of policymakers establishing clear definitions, streamlined negotiation structures, and regional benchmarking to optimize the efficacy and impact of CBAs.

Introduction

Over the past decade, the rapid deployment of renewable energy driven by policy goals, environmental crises, and economic competitiveness has driven an ocean of investment, jobs and tailored benefits into American communities. At least 53 utility-scale renewable energy projects had project delays and cancellations account for potential lost generating capacity of almost 4600 MW between 2008 and 2021, due in part to community opposition among other factors such as long grid interconnection queues and supply chain issues. Over the past decade, community opposition to developments has led clean energy developers to establish CBAs to mitigate impacts. The first such agreement, approved in 2015 between Vineyard Wind and Martha’s Vineyard, included local hiring and off-season construction commitments.

These agreements are generally reached between the developer and either the local government or the local community represented by one or a coalition of community based organizations (CBO). Scholars have published best practices for developers and communities to negotiate CBAs, yet have not directly analyzed emerging trends in the relationship between project scale and agreement value. By benchmarking the monetary value for Community Benefits Agreements in comparison with project nameplate generation capacity, policymakers, community members, and developers can be better informed in aligning agreement funding with project economics.

Definitions

Definitions for Community Benefits Agreements vary between agencies, with some agencies distinguishing voluntary and legally mandated agreements. This fluid use of the term leads to confusion for developers, local governments and host communities. (Source)

Community Benefits Agreements (CBAs): This term encompasses agreements between developers and Community-Based Organizations (CBOs) or local governments. These agreements specify the benefits the developer will offer the community in return for the community’s support of the project. CBAs are legally binding and enforceable in court, ensuring that developers honor their commitments. While the DOE cannot mandate the creation of legally binding agreements between applicants and other parties, it encourages applicants to consider using CBAs and similar agreements in their Community Benefit Plans submissions to enhance accountability and community engagement (Source).

Host Community Agreements (HCAs): Also called Good Neighbor Agreements or Development Agreements, these are agreements between a developer and the host municipality. HCAs aim to mitigate impacts and provide compensation or benefits to offset any adverse effects on the host municipality. Like CBAs, they are legally binding but focus specifically on the operational impacts on host municipalities. (Source)

Community Benefit Plans (CBPs): Unlike CBAs, CBPs are non-binding agreements typically developed by community organizations and developers. They outline the community’s priorities for a development project and the developer’s commitments to those priorities, which can include affordable housing, job creation, local hiring preferences, and more. While CBPs are not legally enforceable, they are required by the Department of Energy (DOE) for all grant opportunities and loan programs under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022. CBPs are evaluated based on their specificity, actionability, and alignment with community and labor engagement, workforce investment, diversity, equity, inclusion, and the Justice40 Initiative. CBPs serve as strategic frameworks rather than enforceable contracts, emphasizing collaboration between developers and communities to address local needs and priorities (Source).

Project labor agreements (PLAs): Project labor agreements are pre-hire collective bargaining agreements between labor unions and contractors that establish the terms and conditions of employment for a specific project. PLAs typically specify wages, benefits and working conditions, and require contractors to source labor through union hiring halls which help connect workers with jobs. They also include methods of dispute resolution to ensure that projects continue without interruption and can include no-strike and no-lockout clauses. (Source) PLAs are required as part of federal construction projects of $35 million or more due to an executive order signed by President Biden in February 2022.

Community Based Organization (CBO): The term “community based organization” has different definitions that depend on policy, location or implementing organization (Source). The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) defines CBOs as nonprofit, non-governmental organizations with a mission to serve and improve specific communities. They must have a strong local presence, a history of community engagement, and the capacity to manage projects related to energy and environmental justice. CBOs are accountable to their communities through member-driven governance and are expected to collaborate with other groups and local governments to achieve community goals.

Key Differences

While Host Community Agreements and Community Benefits Agreements are both legally binding, they differ in enforceability, needs addressed, and challenges posed. Local governments have the clear ability and right to enforce HCAs, whereas the ability of Community-Based Organizations to enforce CBAs depends on their legal standing and the specificity of terms outlined in the agreement (Source). Generally, HCAs address operational impacts on host municipalities and provide compensation or benefits to offset any adverse effects, while CBAs address specific needs of impacted communities. These titles are not yet well defined or widely regulated, with many agreements between host municipalities and project developers being titled a ‘Community Benefit Agreement.’ Negotiating with multiple community groups may yield a more holistic agreement that addresses a broader range of impacts, but can be complicated by involving conflicting interests

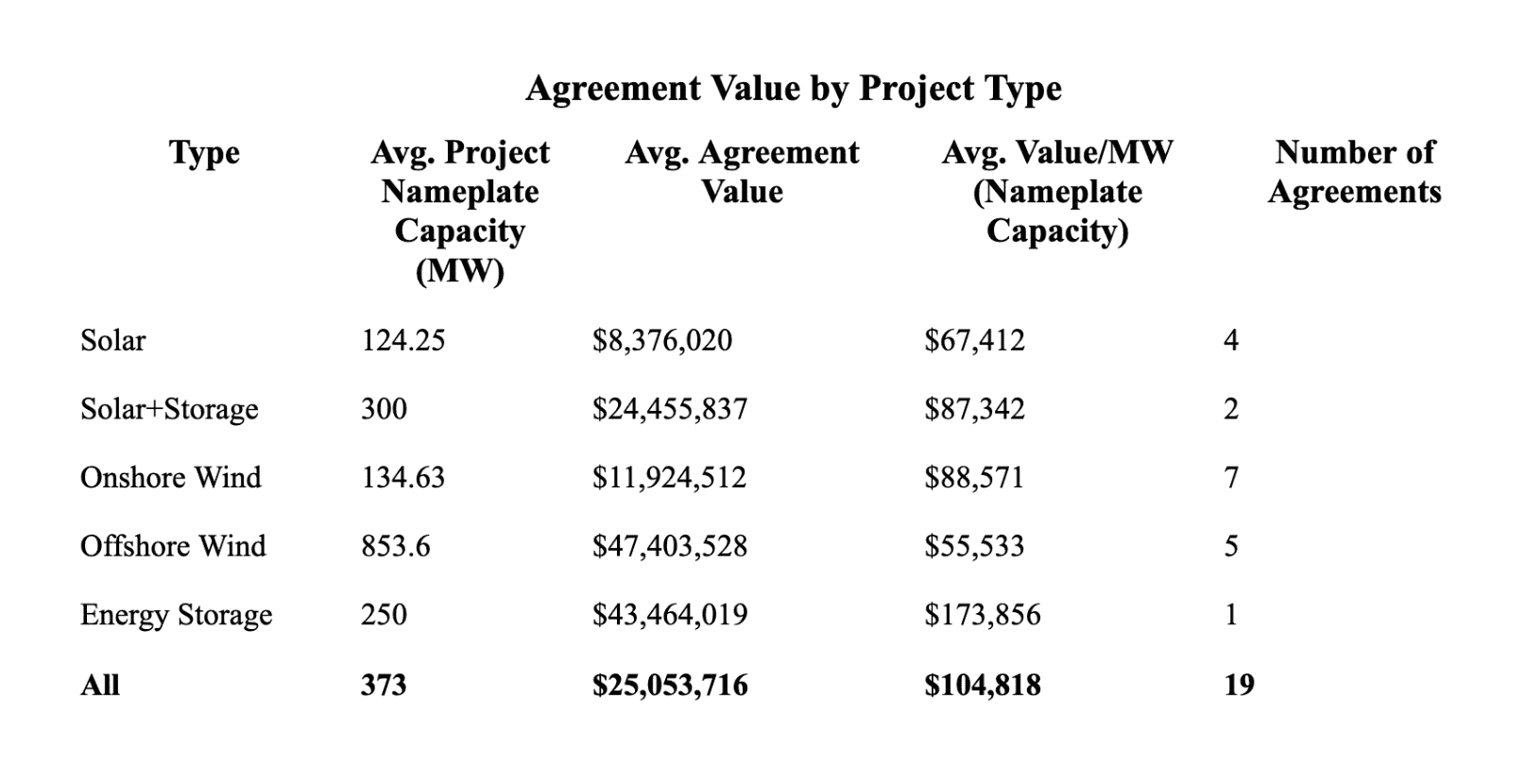

Nineteen clean energy project agreements have been included in this study: seven onshore wind projects, five offshore wind projects, four standalone solar projects, two solar + storage projects and one standalone battery energy storage project. Three offshore wind project developers have committed to but not finalized agreements in part to satisfy the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s requirements for Community Benefit Plans.

Project agreements were sourced from the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law’s Community Benefit Agreement Database, WindXCHANGE Wind Energy Community Benefits Guide, and Community Benefits Agreements; Case Studies, Federal Guidelines, and Best Practices. For agreements lasting throughout project operational life without a specified end date a project life of 20 years was used to create a lifetime agreement value estimate. Three publicly available offshore wind agreements were excluded from the averages because they were not associated with a project with a specific generation capacity; Nantucket and Vineyard Wind, New London and North East Offshore, Morro Bay and Castle Wind. Agreements that only contained hiring, education and outreach commitments were not included. While the data is not yet statistically significant enough to draw concrete conclusions, trends may illuminate how developers, communities and local governments should approach clean energy project agreements.

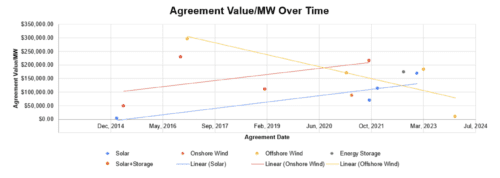

Chart depicts agreement value per project nameplate capacity (MW) over time colored by project type.

Cassadaga Wind entered three parallel agreements with three host towns, represented in this study as one data point since all three agreements were tied to one project/MW generated. Due to the low number of energy storage and solar + storage agreements, trendlines were not included. Trendlines depicted are not statistically significant because of the small sample size and instead depict general trends in wind, solar and storage agreements. Both solar and wind equipment costs have fallen (solar by 90% since 2009 and wind by 49-78% since 2010) while electricity costs have risen steadily, allowing more profit in each project’s budget that can be allocated to community benefits since the model was pioneered in the mid-2010s. The decline in value per MW for offshore wind projects can be attributed to an increased project size without a corresponding increase in agreement value.

Analyzing Trends for Future CBAs

- Regional Benchmarking: As more agreements are reached across regional electricity markets, annual payments determined on a per MW of capacity basis can illustrate regional trends in agreement value.

- Standardized Payment Structure: Out of 19 agreements analyzed, 7 included payments calculated based on the nameplate capacity per operating year, with an average annual standalone payment of $3,540 per MW.

- Inflation Adjustment: Most agreements (all but one) required payments to be increased by 2-3% annually to match expected inflation.

- Market-Based Approach: By identifying benchmark annual payment rates per MW of project nameplate capacity allowable by regional electricity markets, stakeholders can accelerate the signing of mutually beneficial agreements.

Implications for Future CBAs

- Predictable Funding: The trend towards standardized payment structures based on nameplate capacity provides ongoing and predictable funding for communities and local governments.

- Scalability: As clean energy deployment accelerates, benchmarks can help streamline negotiations and ensure fair compensation for communities.

- Balance of Interests: While standardized templates can expedite negotiations, there’s a need to ensure that unique local needs are still addressed through structures like mutual benefits corporations (detailed below).

- Policy Alignment: CBAs can create a positive feedback loop by channeling financial gains from clean energy projects into community benefits, fostering public support for further clean energy deployment.

Case Study: Castle Wind, Morro Bay, CA

Castle Wind LLC was a qualified bidder for the California offshore wind lease auctions but did not secure a lease. Despite this, their Community Benefit Agreement (CBA) and the Morro Bay Mutual Benefits Corporation, which they formed with the City of Morro Bay and commercial fishermen’s associations, are seen as models for Lease Area Use CBAs because it directly mitigated project impacts through a mutual benefits corporation with fishermen’s associations. Castle Wind had negotiated CBAs in 2018 with specific economic benefits for fishermen impacted by their proposed project and secured an exclusive option to lease the Morro Bay outflow tunnel for grid connection. Although Castle Wind did not win a lease in the December 2022 auction, which did not require pre-negotiated CBAs, the mutual benefits corporation model set a precedent for how developers can cooperate with host communities. Winning bidders have the option to join Castle Wind’s Mutual Benefits Corporation agreement or create their own CBAs with relevant communities. (Source)

Case Study: Cassadaga Wind, Chautauqua County, NY

To develop a 126 MW onshore wind project, Cassadaga Wind signed three parallel Host Community Agreements with three host Towns in rural New York, with an annual payment of $504,000. This agreement includes annual payments to each host Town at a rate of $3,800 per MW for each year in operation, increasing after the 6th year of operation by whichever was lower: 2% or percent increase in CPI over previous year. These agreements addressed decommissioning, mitigating impacts to municipal infrastructure, emergency response, noise and construction impact mitigation, a Payment In-Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) agreement between the developer, Chautauqua County Industrial Development Authority, school districts and Towns.

Case Study: Medway Grid, Medway, MA

Medway Grid signed a Host Community Agreement with the Town of Medway for the development of a 250 MW Battery Energy Storage System. Aside from a $42,456,519 Tax Agreement with the Town, the developer agreed to pay; up to $15,000 per year for emergency preparedness training; $20,000 per year for public safety; $100,000 for town to retain independent consultants and counsel; $65,000 for independent study; $50,000 to support master plan renewal; up to $25,000 to each homeowner within 300 feet of project perimeter whose property value was diminished; $250,000 for sidewalk installation; several payments totaling $247,500 to fund a risk reduction and training position in the fire department; $150,000 to an energy conservation and resiliency fund; and $85,000 to an abutting neighbors landscaping fund.

New York State Policy

8 out of 11 clean energy Host Community Agreements and Good Neighbor Agreements identified were reached in New York state. Driven by in part by an order issued on February 11, 2021 in which the New York State Public Service Commission established a “host community benefit program” through which owners of large-scale renewable energy facilities (25 MW+) must pay $500/MW (for solar) or $1,000/MW (for wind) each year for the first 10 years for individual utility bill credit for all residents of the host municipality. Since the issuance of the order the average total value of project Host Community Agreements (above 25 MW threshold) in New York state has increased from $101,029 per MW to $123,330 per MW.

Non-Energy Community Benefits Agreements

Community Benefits Agreements and Host Community Agreements have been signed in order to address community concerns and dissuade opposition to higher education, stadium, mixed-use, shopping mall, mining, industrial parks, and cannabis business developments. The first major CBA signed in 2001 was for the development of the Staples Center in Los Angeles. These agreements generally have less focus on energy and sustainability, generally addressing street and housing upgrades, labor commitments, health impacts, and youth & education. Three cannabis businesses Host Community Agreements included the direct payment of 2-3% of annual gross revenue to the town (Source, Source, Source). In 2005, Georgia Stand-Up secured commitments for the Atlanta BeltLine project through a city resolution, which created the BeltLine Tax Allocation District to fund further community investments (Source). In 2006, the Front Range Economic Strategy Center secured a CBA for the Gates Cherokee Redevelopment Project, featuring an Affordable Housing Plan for low-income residents. In 2018, Stand Up Nashville secured a CBA with Nashville Soccer Holdings for a stadium and mixed-use development, including commitments to affordable housing. Non-energy CBAs have set a precedent for clean energy CBAs by highlighting the need to address diverse community needs beyond environmental concerns.

Future of Community Benefits Agreements

From a project economics perspective, benchmarking the cost of a Community Benefits Agreement can vary based on the cost of electricity in a target market. As more agreements are reached across the country, regional annual payments determined on a per MW of nameplate capacity basis will illustrate regional pricing trends. Out of 16 agreements, 7 included payments calculated based on the nameplate capacity per operating year (6 in NY, 1 in ME) in which the average annual payment is $3,540 per MW. All but one of these agreements required payments be increased by 2-3% annually to match expected inflation. This payment structure addresses the need for ongoing and predictable funding that can be used by communities and local governments for staffing and long term projects and an effectively budgeted cost for project developers.

As the effects of climate change are felt by America’s most vulnerable communities, the need to rapidly decarbonize and electrify requires the expedited deployment of clean energy resources in a fashion that builds community and political support for further clean energy deployment. Although the allocation of funding to meet every community’s unique needs requires in-depth consultation, the underlying funding available in a project’s budget is determined by the price electricity generated can sell for. By identifying benchmark annual payment rates per MW allowable by regional electricity markets, scholars, clean energy proponents, and policymakers can accelerate the signing of mutually beneficial agreements. Community Benefits Agreements create a powerful feedback loop: they channel the financial gains from clean energy projects to meet community needs, which in turn fosters goodwill and public support. This not only aligns with state and federal clean energy goals and incentives but also strengthens the push for essential climate and energy policies.

To minimize the time and labor costs associated with the negotiation and approval of each project, developers often create standard sets of community benefits that may be included with a project. Residents and stakeholders may feel that these benefit templates do not address unique local needs that a developer may not be aware of. The impetus is thus on local policymakers to reduce lengthy and costly negotiation process between developers and community based organizations while still ensuring local needs are addressed. San Diego County Supervisors have directed staff to engage the public and investigate the feasibility of mandatory and voluntary CBA programs for not only renewable energy projects but also warehouses. Although no local program or agreement is the same, Community Benefits Agreements are enforceable and allow community members to actively shape outcomes of project development. Yet to maximize the efficacy of this structure local governments must anticipate the need for CBAs and lay the necessary groundwork.