Non-Energy Benefits and Social Costs: Properly Valuing Distributed Generation

This blog post from the Clean Coalition describes the importance of accounting for Non-Energy Benefits and Social Costs in Resource Planning.

Non-Energy Benefits and Social Costs: Properly Valuing Distributed Generation

Why Accounting for Non-Energy Benefits and Social Costs in Resource Planning is Necessary to Cost-Effectively Usher in California’s Clean Energy Future

As California continues its clean energy transition, it is crucial that Non-Energy Benefits (NEBs) and social costs are fully accounted for in the decision-making process by our regulatory agencies, namely the California Energy Commission (CEC) and the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC), as they evaluate and implement cost-effective investments in infrastructure and resource planning. NEBs are the costs associated with energy production that are not included in the price per kWh of energy. Existing energy prices rely strictly on the cost of energy generation and delivery infrastructure without actively factoring in the full range of impacts based on the generation used, where a generation source is located, and what it takes to deliver energy to end-users. These “other” factors, commonly called externalities by economists, are not unique to the energy industry; externalities are a facet of all capitalist markets. Businesses inherently try to maximize profit by cutting costs across the supply chain to reduce the total price of a product. Yet, the impacts of product development do not simply go away — they are realized in many forms — and even if a consumer is not paying a direct per unit price, society foots the bill in one form or another (i.e., social costs). An effective government limits the true cost to society through regulation, and caps the price presented to the consumer.

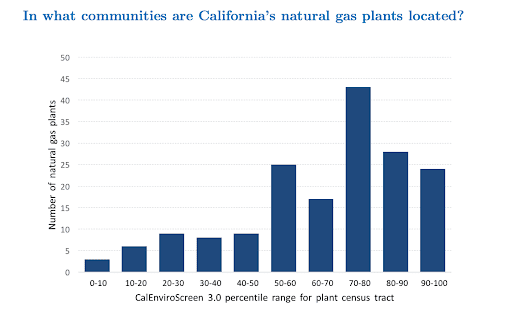

NEBs and social costs exist throughout the process of supplying energy, both positive and negative. We often focus on the negative, since the impacts tend to be more readily apparent in our daily lives. For example, our reliance on fossil fuels has resulted in poor air quality and polluted water. Due in part to terrain, ozone, and activities such as transportation and electricity generation, California’s unhealthy air quality causes respiratory problems, cardiovascular disease, and premature deaths that strain our medical industry. Energy prices include the carbon content of energy generation (e.g., the level of greenhouse gas produced) but not the impact of local pollution or particulate matter emissions. The subsequent costs of increased healthcare spending, lost workdays, and reduced productivity due to climate-related illnesses are overlooked despite being substantial. Even more concerning, these costs overwhelmingly affect disadvantaged communities, within which gas power plants are disproportionately located and access to healthcare remains limited.

50% of gas-fired power plants are located in the 25% most disadvantaged communities.

Water quality and quantity are also significantly affected by gas-fired power plants. In addition to requiring substantial amounts of water for cooling, leading to water depletion in nearby water bodies, these power plants also release chemicals into water bodies during their operation, including heavy metals and nutrients, that lead to oxygen depletion and the death of aquatic life. Likewise, biomass plants have been known to leak sewage into nearby water sources. Disadvantaged communities are disproportionately impacted, exacerbating the existing water crisis that threatens access to clean, reliable, and affordable water.

All distant energy generation — whether renewable or not — depends on costly transmission lines to deliver power, harming California’s pristine natural lands. While renewable resources do not pollute in the same manner as fossil fuels, they do require vast tracts of land to be cleared, leading to habitat loss and the disruption of ecosystems.

In contrast, distributed energy resources (DER) like rooftop solar and battery storage avoid many of these external costs and create positive externalities. DER eliminate the need for long transmission lines, which could save ratepayers hundreds of billions of dollars over the coming decades, while preserving the environment. DER deployed on the built environment (e.g., rooftops, parking lots, and parking structures) avoid land use impacts, minimizing ecological disruption. Moreover, DER lay the foundation for Community Microgrids, enabling energy resilience in the face of increasingly common natural disasters and obviating gas plants. These microgrids can operate independently of the central grid during outages, ensuring that communities have access to reliable power in emergencies, a crucial advantage that distant energy generation cannot offer.

It is clear that in order to make the most accurate decisions about cost-effectiveness, and to subsequently select the proper portfolio of resources, the consideration of externalities is essential. Failing to consider NEBs and social costs in energy prices ignores the true cost to society, implying that the business-as-usual approach is sufficient, rather than focusing on minimizing the total cost, monetary and otherwise, imposed on Californians.

Recent Updates in California

Thus far in 2024, the CEC and CPUC have taken the first of many steps required to value NEBs and social costs and effectively include these costs in the resource planning framework used to determine cost-effectiveness. The Clean Coalition joined a coalition led by the Center for Biological Diversity to successfully petition the CEC to properly consider NEBs and social costs, noting that existing work by regulatory agencies has been insufficient and that local environmental impacts of fossil fuel-based energy production “fall disproportionately on disadvantaged and other environmental justice communities.”

In approving the petition, the CEC agreed to open a Rulemaking that will consider NEBs and social costs, beginning the dialogue required to catalog the different externalities that exist and attempt to ascribe a nonzero value to each one. The law that created the CEC, the Warren-Alquist Act, requires the CEC to, “minimize the cost to society of the reliable energy services that are provided by natural gas and electricity, and to improve the environment” and “include a value for any costs and benefits to the environment, including air quality” in cost-effectiveness determinations. Evaluating NEBs and social costs when making resource planning and investment decisions is particularly critical because the electricity transmission and distribution system is run by private Investor Owned Utilities, where the model of continuous profit and growth has caused massive cost-externalization.

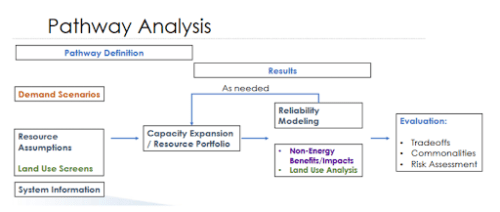

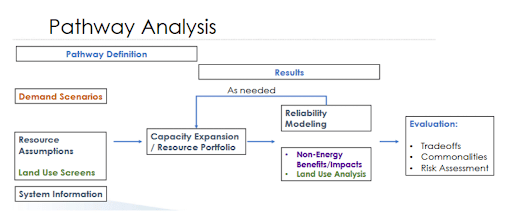

Pathway Analysis used in the development of the SB 100 Report to determine the resource portfolio needed achieve California’s climate and energy goals on schedule

Under the existing capacity modeling methodology, NEBs and social costs are factored into the results of the various resource planning scenarios that are modeled to determine the tradeoffs that exist in the ultimate scenario adopted by the CEC. NEBs and social costs are effectively siloed, an afterthought to the process when they should be fundamental inputs that guide the different resource scenarios being modeled. For example, the existing modeling results in very little consideration of DER, whereas using NEBs and social costs as inputs would emphasize the resilience value of DER and the local health impacts, likely resulting in the selection of a very different resource mix that includes far more DER.

While the CEC has begun to determine how NEBs can more effectively be considered in resource planning, the CPUC has focused on cost-effectiveness. The Clean Coalition provided significant input in urging the creation of a Societal Cost Test (SCT) that factors NEBs and social costs in calculating the benefit-cost ratio of DER programs. The CPUC chose to adopt a first version SCT as an informational test for use in all DER-related proceedings to supplement the measurement of the total costs and benefits of a given program. The SCT includes four inputs-a societal discount rate of 3%, a social cost of carbon (a base value of $53 and a high value of $155, in 2020 dollars), an air quality adder of $14/MWh, and a methane leakage adder of 2.3%.

The CPUC’s decision to mandate the inclusion of NEBs and social costs in DER cost-effectiveness testing, as well as the creation of a new Rulemaking by the CEC to integrate costs in resource planning, represent significant steps forward in capturing the true value of DER. To achieve California’s climate and energy goals and deliver the greatest value to the ratepayers, DER must be part of the answer. In the long run, accurate accounting of resource costs and benefits will save the ratepayers hundreds of billions of dollars, as decision makers come to understand that the business-as-usual approach of predominantly relying on remote resources delivered via transmission infrastructure is economically and environmentally suboptimal – and would greatly delay the transition to the renewables-driven energy future.

Remaining Challenges and Recommendations

For the CPUC, major opportunities remain in the development of a more accurate SCT.

First, as adopted, the CPUC plans to use the SCT as a purely informational test, rather than as the primary cost-effectiveness test in evaluating all DER programs. While the CPUC’s decision to use the SCT to inform the decision-making process is a step forward, not instituting it as a primary cost-effectiveness test calls into question whether the results of the SCT will be properly considered and balanced against other tests. Second, the SCT fails to consider the value-of-resilience (VOR). DER such as local solar, battery storage, and electric vehicles set the stage for the deployment of Community Microgrids, which enable critical facilities to remain operational during power outages. These critical facilities, which include hospitals, fire stations, emergency shelters, can serve entire communities during times of crisis.

As the Clean Coalition has argued in numerous proceedings and venues, resilience is often recognized as a nonzero value stream. However, if not directly factored into cost-effectiveness testing, then its value is effectively treated as zero. To address this gap, the Clean Coalition has developed a framework (known as the VOR123 methodology) to assign an economic value of resilience, ensuring that its benefits are properly accounted for. Incorporating a system-wide value that can be incorporated in a cost test or planning methodology will provide a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the true value of DER, leading to more informed energy decisions and setting the stage for a resilient clean-energy future.

Thirdly and finally, the CPUC must eliminate the claim that a socially and environmentally responsible portfolio will increase utility rates, for the above mentioned reasons and because such a declaration fails to acknowledge that NEBs/social costs are paid for by (or benefit) Californians regardless of inclusion in utility rates. The only way to promote lasting change, and lower true rates in the long-term by fixing existing market distortions, is to fully utilize the SCT in the resource planning and investment decision making process.

“There are clearly reasons for rate increases, independent of NEBs and social costs, which DER can help avoid but which are yet to be adequately reflected in the Commission’s cost-effectiveness tests”

For the state to make informed investment decisions in its transition to clean energy, full consideration of the externalities caused by its energy portfolio is crucial. Ignoring these externalities distorts the true value of that portfolio to society, and will leave Californians burdened with significant costs outside of the price paid for energy. The CEC’s recent decision to open a proceeding on NEBs signals a transformative shift in the right direction. But a full accounting of NEBs and inclusion into the decision making process is needed. By integrating the broader social and environmental impacts of an energy resource into cost-effectiveness testing and the resource planning framework, California is moving towards making decisions based on the true cost of a resource. In a future where all NEBs, including resilience, are fully embedded into investment strategies, all Californians, including those in disadvantaged communities, will experience the rewards of a sustainable, resilient, and equitable energy grid.