EIFDs: A new way to pay for Solar Microgrids

This blog posts presents EIFDs as a way to fund Solar Microgrids.

EIFDs: A new way to pay for Solar Microgrids

By Erik Hagstrom and Haley Weinstein

California faces significant energy challenges as it works toward ambitious climate goals—achieving 60% renewable energy by 2030 and 100% by 2045. These goals demand innovative solutions to overcome rising electricity costs, grid capacity limitations, and growing demands for reliable energy. For local governments, particularly in rural areas, these challenges also represent an opportunity: to drive economic growth while enhancing energy resilience.

Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts (EIFDs) offer a powerful tool to bridge this gap. By financing Solar Microgrids, EIFDs can unlock transformative benefits for local economies, particularly in agriculture, which forms the backbone of California’s economy by producing one-third of the nation’s vegetables and two-thirds of its fruits and nuts. Solar Microgrids provide reliable, cost-effective, and sustainable energy solutions that support economic development while reducing dependency on the grid.

Through the strategic use of EIFDs, local governments can catalyze projects that deliver economic, environmental, and resilience benefits. By reinvesting increased property tax revenues from these developments, municipalities can finance Solar Microgrids without imposing additional burdens on taxpayers. This approach enables California’s communities to meet their clean energy goals while fostering growth in agriculture, industry, and beyond.

Legal Framework in California

Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts (EIFDs)

EIFDs, introduced in 2014 through SB 628, serve as a modern alternative to the traditional Tax Increment Financing (TIF) tools once employed by California’s redevelopment agencies (RDAs). RDAs were dissolved in 2012 due to concerns over mismanagement and their impact on school funding. In response, EIFDs were designed to provide cities, counties, and special districts with a transparent, collaborative mechanism to finance infrastructure and economic development projects without imposing new taxes on property owners.

Unlike their predecessors, EIFDs allow for increased property tax revenue generated within the district to be reinvested in operations, maintenance, and expansion. Under AB 116, while voter approval is no longer necessary for bond issuance, EIFDs must comply with increased public engagement obligations during their formation and bond issuance processes.

Key features of EIFDs include:

- Broad Financing Scope: Support for diverse public works projects, such as transportation, affordable housing, parks, libraries, and brownfield restoration.

- Regional Collaboration: Opportunities to leverage increases in property tax value for shared benefits across communities. Districts can encompass entire cities, counties or combinations of both.

- Flexible Bond Issuance: The ability to issue bonds without a public vote (as of 2019), enabling infrastructure financing over a 45-year period.

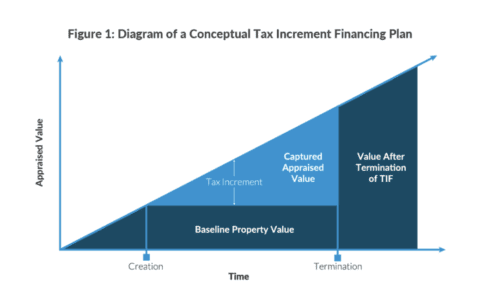

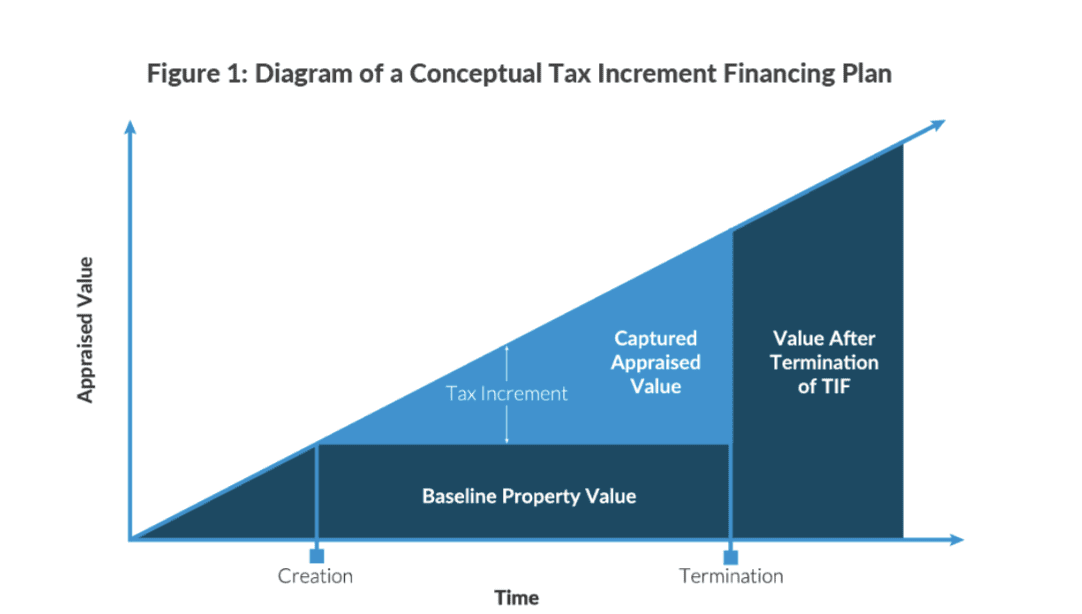

While this diagram illustrates the concept of Tax Increment Financing (TIF), of which Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts (EIFDs) are a subcategory. EIFDs operate by capturing the tax increment from rising property values but are distinct from more traditional TIF structures by excluding school funds, incentivizing local collaboration, and supporting a broader range of community projects (Citizens Budget Commission, 2017).

EIFDs empower cities, counties, and special districts to finance a wide range of public works projects, including transportation, affordable housing, parks, and brownfield remediation. Crucially, EIFDs can also fund innovative energy solutions like Solar Microgrids, which provide critical benefits for resilience, economic development, and environmental sustainability.

To establish an EIFD, local governments must follow these steps:

- Form a Public Financing Authority (PFA): A governing body consisting of representatives from participating entities and community members.

- Develop an Infrastructure Financing Plan (IFP): A detailed roadmap outlining project objectives, costs, and funding sources.

- Conduct community engagement to gather public input and secure approval.

For more on EIFDs, visit California Association for Local Economic Development or Planetizen.

The Potential of Solar Microgrids

A Solar Microgrid is a localized energy system that integrates solar energy generation with storage, capable of operating both in connection with the larger grid and independently (“islanding”) during grid outages. These systems are specifically designed to ensure reliable, cost-effective, and sustainable energy without reliance on incumbent utilities. As spotlighted in the Clean Coalition’s Community Microgrid Initiative, Solar Microgrids offer an unparalleled trifecta of economic, environmental, and resilience benefits, making them a key solution for renewable energy deployment.

By adopting Solar Microgrids, communities, industrial developments, and critical facilities can unlock the following advantages:

- Resilience: Enhanced energy resilience during blackouts, public safety power shutoffs (PSPS), and natural disasters.

- Economic Savings: Lower operational costs through reduced reliance on grid energy and avoidance of peak pricing.

- Sector Support: Stable energy supply for industrial and agricultural operations, minimizing disruptions that could harm production and profit margins.

- Efficient Deployment: Faster energy provision compared to investor-owned utilities (IOUs), avoiding long queues and delays that typically span 1.5–5 years depending on the project scale.

For a detailed methodology on quantifying resilience benefits, refer to the Clean Coalition’s Value of Resiliency (VOR) approach. While many local governments have implemented Solar Microgrids for communities and critical facilities through the Community Microgrid Initiative, the scope of these projects should expand. Agricultural and industrial developments stand to gain significantly from these systems, advancing local economic development while achieving the unparalleled trifecta of economic, environmental, and resilience benefits.

Examples of Successful Ag-Industrial Solar Microgrid Projects

While private industry has made significant progress in implementing Solar Microgrids, local governments have substantial untapped potential to leverage Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts (EIFDs) to drive agricultural and industrial growth. By establishing EIFDs, municipalities can support the construction of Solar Microgrids that enhance existing developments and incentivize new ones. This approach provides a supplemental financing mechanism that delivers external benefits, such as improved operations for nearby ranchers and farmers, increased employment opportunities, and expanded tax revenues.

Solar Microgrids not only improve operational efficiency and reduce costs but also play a critical role in strengthening the resilience of our food systems against climate change. By facilitating the transition to Solar Microgrids, local governments can unlock transformative economic development cycles while addressing urgent environmental challenges.

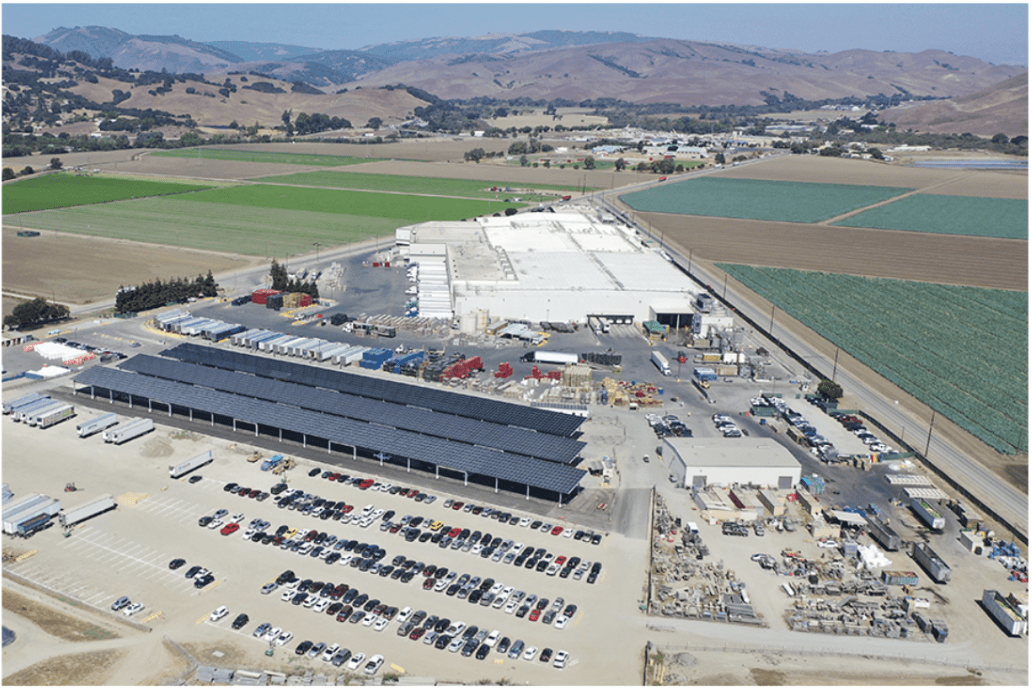

Source: Taylor Farms Microgrid in San Juan Bautista.

Notable examples of successful private Solar Microgrids include:

- Taylor Farms Microgrid – San Juan Bautista, CA (2022)

- Energy System: 6 MW Bloom fuel cells, 2 MW solar energy generation, and 2 MW/4 MWh battery storage.

- Impact: Powers a 450,000-square-foot facility, addressing grid reliability issues and reducing high energy costs.

- Partners: Bloom Energy, Ameresco, Concept Clean Energy (source).

- Spreckels Sugar Company Solar Microgrid – Brawley, CA (2021)

- Energy System: Ground-mounted solar energy panels (2.4 acres) and Tesla Powerpacks (880 kWh storage).

- Impact: Reduces greenhouse gas emissions by over 500 metric tons annually and delivers $9.2M in energy cost savings over 30 years.

- Developer: Clean Focus Renewables, Altaterra Energy (source).

- Harborside Inc. Microgrid – Salinas, CA (2021)

- Energy System: 4.9 MW solar energy generation and 6 MWh battery storage with automated load management.

- Impact: Achieved $12.5M in energy cost savings over 20 years.

- Developer: Scale Microgrid Solutions (source).

- Bowery Farming Solar Microgrid – Kearny, NJ (2021)

- Energy System: Indoor farming facility powered by 150 kW solar generation, 200 kW storage, and dispatchable gas generation.

- Impact: Fully independent operations during outages, supporting sustainable indoor agriculture.

- Developer: Scale Microgrid Solutions (source).

Solar Microgrid Policy and Regulations

Solar Microgrid development in California has gained significant traction under SB 1339 (2018), which directed the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) to expedite microgrid commercialization. The CPUC now administers key initiatives that support Solar Microgrids, including:

- Microgrid Incentive Program: A $200 million competitive grant program that funds projects through Investor-Owned Utilities (IOUs). This program focuses on assisting disadvantaged and vulnerable communities affected by grid outages, facilitating the development of multi-property microgrids to bolster energy resilience at the local level.

- Community Microgrid Enablement Tariff (CMET): Adopted in 2022, CMET simplifies regulatory processes, making it easier for local governments and developers to deploy Solar Microgrids. While not as comprehensive as some alternative models, CMET represents a practical framework within the current regulatory environment.

The Clean Coalition has championed the Resilient Energy Subscription (RES) model as an innovative approach to achieving clean, resilient energy access. This subscription-based service guarantees energy resiliency, with customers paying a monthly fee to cover the development and maintenance of Solar Microgrids. RES enables incremental expansion by adding subscribers or scaling generation and storage assets as demand grows. However, despite its potential to deliver tailored, localized energy solutions, the RES model has been largely overlooked by the CPUC in favor of IOU-driven programs like CMET.

While CMET remains the primary regulatory mechanism for microgrid deployment, the Clean Coalition continues to advocate for the adoption of RES as a more flexible and community-centric approach. Together, these frameworks reflect California’s progress toward advancing renewable energy and achieving the unparalleled trifecta of economic, environmental, and resilience benefits offered by Solar Microgrids.

Using EIFDs to Finance Solar Microgrid Projects

Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts (EIFDs) offer local governments a powerful tool to finance Solar Microgrid development. Local governments should consult with experts in property tax policy and EIFD formation prior to taking the following steps:

- Initiate EIFD Creation: Adopt a resolution of intent to establish an EIFD.

- Form a Public Financing Authority (PFA): Include stakeholders from taxing entities and public members.

- Develop an Infrastructure Financing Plan (IFP): Detail the microgrid project, costs, and tax increment funding sources.

- Engage the Community: Explain the benefits of Solar Microgrids and EIFDs.

- Secure Approvals: No voter approval is needed to form an EIFD. Bond issuance does not require voter approval, but PFA must hold 3 public hearings to receive input and guidance from the public.

- Collect Tax Increment: EIFDs can finance Solar Microgrids over 45 years, with options for phased implementation and developer contributions.

- Explore Funding Partnerships: Combine EIFD funds with state/federal grants, infrastructure bank loans, or power purchase agreements (PPAs).

For more on Solar Microgrid financing, see NREL’s Guide to Financing Microgrids.

Benefits of EIFD-Funded Solar Microgrids

EIFD-funded Solar Microgrids deliver a range of benefits:

- Enhanced Energy Resilience: Protect communities and industries from outages and PSPS disruptions.

- Support for Renewable Energy Goals: Advance California’s clean energy targets.

- Economic Development: Stable energy supply fosters industrial growth and reduces operational costs for incoming and existing users.

- Grid Stability: Reduce strain on the larger grid, improving overall reliability for non-microgrid users.

- Funding for Operations and Maintenance: EIFD funding eligible to be used for ongoing or capitalized costs to maintain public capital facilities financed in whole or in part by the district

Risks and Obstacles

Despite their potential, EIFD-funded Solar Microgrids face several obstacles:

- Regulatory Challenges: Export limits (e.g., 20 MW under CMET) and public bidding processes for private microgrid operators can delay projects.

- Technical Complexities: Reliable energy storage, isolation devices, and solutions for intermittent energy generation are essential but challenging.

- Financial Risks: The success of EIFDs relies on growth in property values, accurate demand projections, and well-planned economic development strategies.

- Utility Collaboration: Cooperation with Investor-Owned Utilities (IOUs) and Community Choice Aggregators (CCAs) is critical for project feasibility and grid integration.

Local governments considering EIFD-funded microgrids should begin by assessing grid capacity to identify potential barriers and opportunities for development. Local governments can utilize EIFDs to build microgrids for either their whole jurisdiction or a specific priority area. Community engagement is crucial to ensure that microgrid solutions align with local needs and priorities, fostering trust and support among stakeholders. Collaboration with Community Choice Aggregators can offer valuable technical expertise and help facilitate Power Purchase Agreements, streamlining the development process.

Phased implementation is an effective strategy to manage upfront costs while enabling incremental expansion as demand grows. By leveraging EIFDs, local governments can overcome grid limitations, drive sustainable development, and catalyze economic growth in rural and agricultural communities. These tools empower leaders, economic development directors, and planners to transform challenges into opportunities, advancing energy resilience and achieving California’s clean energy goals.

For further reading, visit the NREL State, Local, and Tribal Program.