Slouching toward a California microgrid tariff

What will it take to fulfill SB 1339’s promise of commercializing microgrids across the state?

California has always been a clean energy leader. The state should be continuing this venerable tradition with its microgrid legislation, SB 1339, which has the commendable goal of facilitating the commercialization of microgrids in California.

Given the urgent need for energy resilience in California’s new normal of increasingly severe wildfire seasons and continuing planned utility outages, the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) proceeding tasked with implementing SB 1339 should be paving the way for microgrid proliferation in the state. Renewables-driven Community Microgrids, in particular, bring our communities an unparalleled trifecta of economic, environmental, and resilience benefits. With lowered air quality from ever-longer wildfire seasons coupled with economic woes related to the pandemic, all of these benefits are crucial for California.

Since 2019, the Clean Coalition has been active in the SB 1339 proceeding, arguing in our filings for these elements and more:

- Creating standard tariffs for microgrids in California that:

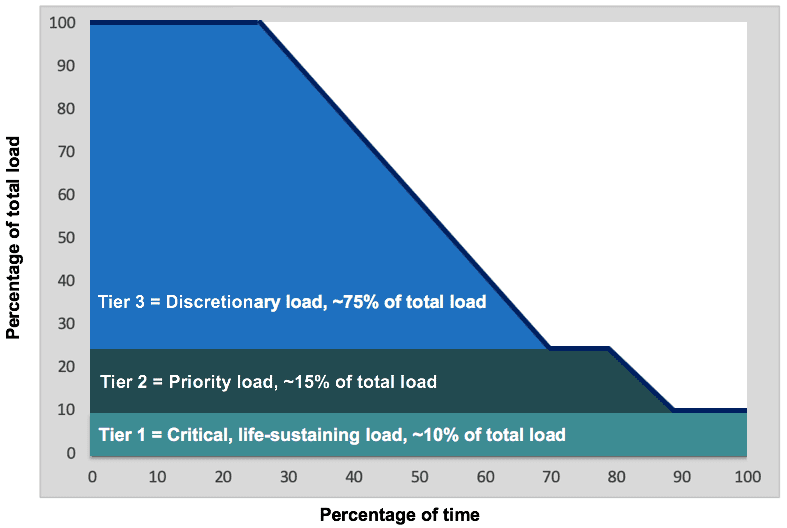

- Properly value the resilience provided by renewables-driven microgrids, using the Clean Coalition’s value-of-resilience (VOR123) methodology.

- Properly value the resilience provided by renewables-driven microgrids, using the Clean Coalition’s value-of-resilience (VOR123) methodology.

-

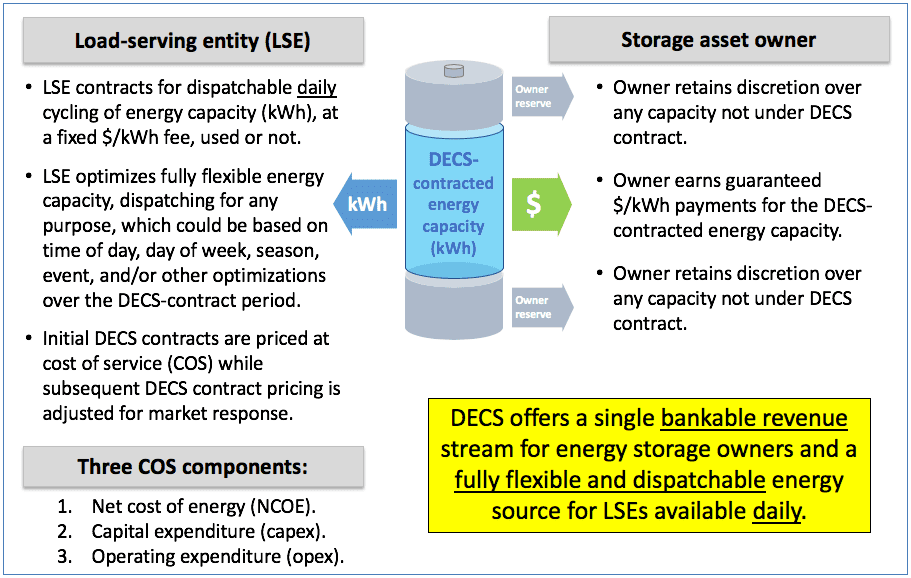

- Provide value streams for the secondary markets that microgrids can participate in and the ancillary services microgrids provide when not in island mode. Alternatively, all the value streams can be aggregated into a single straightforward Dispatchable Energy Capacity Services (DECS) contract with a load-serving entity (LSE).

- Cover both behind-the-meter (BTM) and front-of-meter (FOM) solar+storage microgrids.

- Provide value streams for the secondary markets that microgrids can participate in and the ancillary services microgrids provide when not in island mode. Alternatively, all the value streams can be aggregated into a single straightforward Dispatchable Energy Capacity Services (DECS) contract with a load-serving entity (LSE).

- Adopting a market-responsive Feed-In Tariff (FIT), like the one the Clean Coalition designed for the City of San Diego, to facilitate the procurement of renewable resources for microgrids, with a Dispatchability Adder to incentivize energy storage.

- Streamlining interconnection for microgrids.

Thus far, though, SB 1339 has not lived up to its promise due to the conservative approach being taken by the CPUC.

Little progress so far

Track 1 of the three tracks in the proceeding focused on the urgent short-term need for California’s investor-owned utilities (IOUs) to develop microgrids before the start of the 2020 wildfire season.

By the time an early, and already severe, wildfire season hit the state in August 2020, little progress had been made; Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) contracted for 350 megawatts (MW) of diesel generation in resilience zones, while the other two major California utilities, San Diego Gas & Electric (SDG&E) and Southern California Edison (SCE), claimed to already have microgrid projects in the works. Interestingly, SCE cited the Montecito Community Microgrid Initiative (MCMI) in its service territory as evidence of progress, despite the utility’s lack of cooperation on this initiative; the MCMI is being led by the Clean Coalition in collaboration with numerous Montecito critical community facilities and other key stakeholders.

In the end, Track 1 resulted in a compromise: The CPUC ruled that any diesel generator solutions must be temporary and are to be replaced by adequate renewables-driven solutions in 2021. More recently, lack of progress at the CPUC seemed to indicate that even this plan may be derailed.

Track 2, currently in progress, provides an opportunity for the microgrid proceeding to get into the serious nuts and bolts of implementing SB 1339, focusing on medium-term solutions including developing rates and tariffs. However, the CPUC has continued its conservative approach in this track.

The July 2020 Staff Proposal for Track 2 (see p. 14 of the PDF), while it made some important progress, fell short of facilitating microgrid commercialization. The proposal focused on BTM microgrids and failed to clearly define a FOM Community Microgrid –which multiple parties to the proceeding agree is a microgrid that consists of multiple end-use customers and energy resources at multiple points of interconnection to the utility distribution system, and that uses existing utility distribution feeders when operating in island mode.

The proposal’s primary focus on exemptions for departing load and other charges, as well as on BTM microgrids at critical facilities owned by municipal corporations, is extremely limiting. And while the proposal defines a tariff for specific microgrids when used for emergency backup power, it omits a more general tariff. (See more in this filing and this filing from the Clean Coalition.)

In addition to the Track 2 proposal, the CPUC staff released a Concept Paper (p. 59 of the PDF) that delves into many of the details omitted in the proposal and even cites the Clean Coalition’s VOR123 methodology (p. 94 of the PDF). However, the Concept Paper is intended only for staff use in preparation for Track 3, and comments on it will not be part of the Track 2 proceeding record.

Why we need a microgrid tariff

Why is a general tariff so important for microgrid proliferation?

Microgrids are made up of multiple technologies, may have complex ownership structures, and come with various costs that may be borne by different parties. Standardized tariffs that can be applied to any microgrid project could account for all of these complexities.

In addition, microgrids provide numerous benefits that need to be part of microgrid valuation – including the most obvious one: resilience. But resilience accounts only for a microgrid’s value during grid outages. Microgrids can also provide numerous benefits during normal (blue-sky) operations, such as grid services like demand-side management, voltage support, and deferral of grid infrastructure upgrades.

Microgrid tariffs are crucial to compensate microgrids for use during blue-sky operations, access to wholesale and secondary markets, and options for sharing electricity with other parties. The lack of such tariffs makes it difficult to commercialize microgrids.

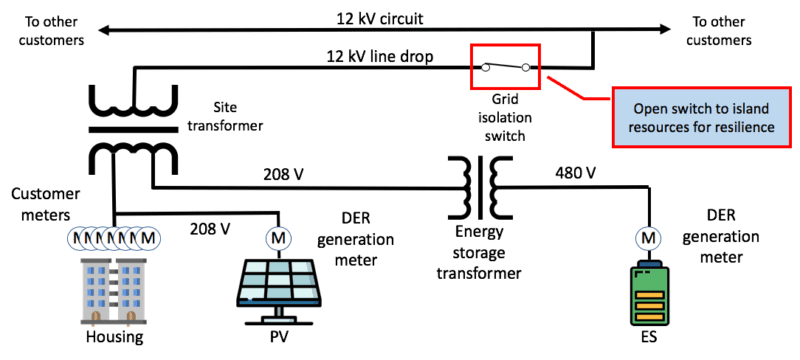

A case in point is the Clean Coalition’s Valencia Gardens Energy Storage (VGES) Project, a partnership with PG&E and the California Energy Commission (CEC). Designed to enhance the solar hosting capacity of the existing feeder by at least 25% – allowing far more solar to be sited on that feeder – this project will add FOM energy storage to a low-income and senior housing facility in San Francisco’s Mission District that already has 580 kilowatts (kW) of FOM solar.

The following diagram shows the existing solar and planned energy storage, as well as the project’s potential for a future Community Microgrid. Because the project includes FOM solar and energy storage, creating a Community Microgrid would require simply installing a grid isolation switch, as indicated by the red box in the diagram – providing the hundreds of low- income and senior residents at the Valencia Gardens Apartments with significant resilience.

However, the value proposition of this system is not just resilience – as important as that is – but also the ability to participate in wholesale energy markets and provide ancillary services. The problem, however, is that the value streams are complex, fragmented, and generally too expensive to access. VGES provides just one example of the need for microgrid tariffs that compensates for resilience without limiting microgrid functionality to resilience.

A microgrid tariff model: The Redwood Coast Airport Microgrid

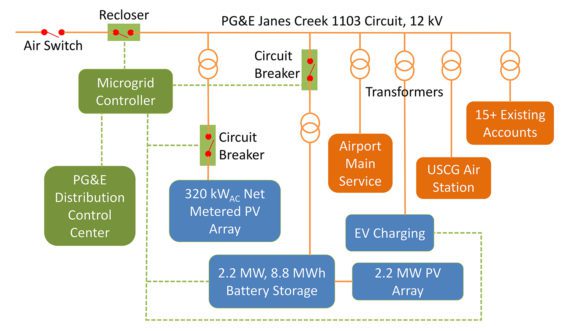

Creating microgrid tariffs is not simple, but it’s being tackled already for the Redwood Coast Airport Microgrid (RCAM) in Humboldt County, an innovative partnership between the local community choice aggregator (CCA), Redwood Coast Energy Authority (RCEA); the Schatz Energy Research Center at Humboldt State University; and PG&E. The Clean Coalition’s Executive Director is on the RCAM Technical Advisory Committee.

A complex project involving multiple facilities, a CCA, and PG&E customers, RCAM will be the first FOM, multi-customer microgrid in Northern California and is staging to be a leading Community Microgrid showcase anywhere. (For more, see our RCAM webinar.)

The project will feature a 2.2 MW solar array and a 2.2 MW/8.8 megawatt-hour (MWh) battery storage system. In blue-sky operation, the microgrid will be used to participate in the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) wholesale market. During grid outages, RCAM will go into island mode with RCEA in control of what is normally PG&E’s distribution feeder segment.

To enable this arrangement, the project team is developing agreements, processes, procedures, and protocols that outline roles and responsibilities and address the need to share costs and benefits. The Clean Coalition and other parties are advocating that lessons learned through this process be used as a model for a Community Microgrid tariff in the CPUC microgrids proceeding.

Five key questions

What goes into creating a microgrid tariff? A good guide can be found in five key questions that must be answered to provision resilience for microgrids, in particular for Community Microgrids:

- What distribution automation solutions are required to achieve the needed Community Microgrid functionality during grid outages? These may include line-segment sectionalizing equipment and Monitoring, Communications, and Control (MC2) solutions. Proposal 5 of the Track 2 Staff Proposal calls for the IOUs to test other low-cost reliable methods of electrical isolation, including using smart meters and reconfiguring current electrical equipment.

- What costs are associated with the distribution automation solutions? Upfront capital expenditures (capex) and ongoing operating costs (opex) need to be evaluated; for Community Microgrids, this includes the cost of distribution grid upgrades.

- Who owns the Community Microgrid and/or its key components? A major inhibitor for Community Microgrids remains the over-the-fence rule (PUC §218), which makes the most likely iteration of a Community Microgrid one in which the IOU owns the electrical infrastructure and operates the microgrid. Changing this would unlock the true potential of Community Microgrids like the Montecito Community Microgrid Initiative (MCMI). As demonstrated in the block diagram below, the three initial sites for the MCMI are all located on the same feeder segment, making them perfect for a Community Microgrid made up of FOM solar+storage microgrids. But the over-the-fence rule limits the sites to using BTM microgrids for resilience at each separate site.

- Who operates the Community Microgrid during grid outages? In most cases, this will be the utility. However, the microgrids proceeding has been inadequate when it comes to accounting for or defining Community Microgrids, so this question has not been clearly answered. Using the RCAM project as a model could help provide clarity on this question.

- How does the utility recover its costs? A Community Microgrid brings ratebase opportunities for providing resilience to critical community facilities and fee opportunities when the resilience is delivered to specific customers only. These fees could be as simple as an adder for resilience. The Clean Coalition and other parties are recommending that microgrids be exempt from fees if they provide community-wide benefits like resilience. The IOUs, however, have claimed that because there is no value of resilience, this exemption could be considered cost-shifting. That’s the same tired cost-shifting argument that’s been used for years in attempts to do away with net energy metering (NEM), which has been shown to benefit all utility customers. Moreover, the Clean Coalition has shown that resilience does provide a quantifiable value; therefore, that value should be accounted for.

What comes next?

As Track 2 of the microgrid proceeding continues, the Clean Coalition and other parties are advocating that the CPUC develop an initial microgrid tariff by the end of 2020 and a multi-customer microgrid tariff in the first half of 2021. It is unclear whether the CPUC will make this a priority.

Track 3 will focus on finding long-term solutions and finalizing the requirements of SB 1339 – something that was originally scheduled to be done by the end of 2020. A permanent working group will be created to focus on microgrids, with an emphasis on ensuring that microgrids provide resilience, as well as on streamlining interconnection for microgrids.

These are laudable goals, but to achieve them the CPUC must adopt a more forward-looking approach than it has to date. The Clean Coalition will continue working hard in this proceeding to ensure that California has a path to commercialize – and thus proliferate – all types of microgrids.